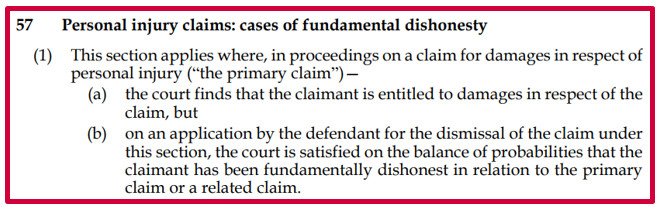

Mr. Justice Knowles, who formulated the leading authority on dismissal of a claim under s.57 of the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015, in the case of LOCOG v Sinfield [2018] EWHC 51 (QB), has, this week, handed down judgment on the disapplication of qualified-one-way costs shifting (QOCS), owing to ‘fundamental dishonesty’.

In LOCOG, the High Court Judge imported language, used by His Honour Judge Moloney QC’s ruling in Gosling v Hailo & Anor (29 April 2014, Cambridge CC), to reason that a personal injury claimant could be described as ‘fundamentally dishonest’, within the scope of s.57(1)(b):

‘... if the defendant proves on a balance of probabilities that the claimant has acted dishonestly in relation to the primary claim and/or a related claim (as defined in s 57(8)), and that he has thus substantially affected the presentation of his case, either in respects of liability or quantum, in a way which potentially adversely affected the defendant in a significant way, judged in the context of the particular facts and circumstances of the litigation. Dishonesty is to be judged according to the test set out by the Supreme Court in Ivey v Genting Casinos Limited (t/a Crockfords Club), supra.

By using the formulation 'substantially affects' I am intending to convey the same idea as the expressions 'going to the root' or 'going to the heart' of the claim. By potentially affecting the defendant's liability in a significant way 'in the context of the particular facts and circumstances of the litigation' I mean (for example) that a dishonest claim for special damages of £9000 in a claim worth £10 000 in its entirety should be judged to significantly affect the defendant's interests, notwithstanding that the defendant may be a multi-billion pound insurer to whom £9000 is a trivial sum’.

More recently, Knowles J heard an appeal of a trial on liability, which a road-traffic accident (RTA) claimant had lost.

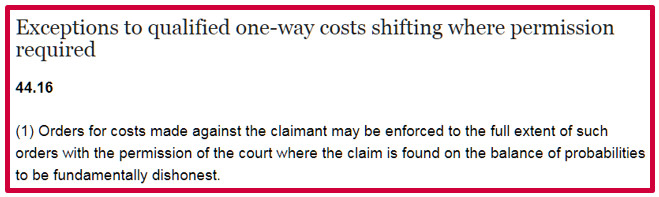

The claimant appealed against the trial Judge’s decision, on the grounds that the defendant had been negligent, while the defendant cross-appealed that the claim should have been found to be ‘fundamentally dishonest’, in respect of the credit-hire element. It therefore sought to recoup the costs of defending the claim, which, but for CPR 44.16(1), were irrecoverable.

At 1st instance, His Honour Judge Tindal described the claimant as ‘basically an honest man’ and conceded that the claimant’s ‘inconsistencies’ could be ‘explicated’ by the fact that he was ‘was trying to recall events four years ago’.

On appeal, the defendant submitted that the trial Judge had reached the wrong outcome, because ‘the Claimant made a false disclosure statement in his List of Documents, which was verified by a statement of truth ... which the Claimant then compounded in his reply to the Defendant’s Part 18 questions’ and this constituted ‘fundamental dishonesty’.

Was this a ‘dishonest’ claim?

Although Knowles J acknowledged that ‘difficulties in recollection relating to a fleeting incident some years previously’ did not exemplify ‘dishonesty’, let alone ‘fundamental dishonesty’, he concluded that the non-disclosure in question was ‘plainly dishonest’:

‘The questions he was asked were not difficult (and he did not say that he had not properly understood them); they were in writing; he had time to consider his documentation; and he had the opportunity to take legal advice if he was unsure about how to answer and what to disclose ... Nor ... could the Claimant’s failure be explained on the grounds that he was being asked to recall events from four years previously.

... This was not simply a case where there had just been “not particularly good” disclosure by the Claimant. He deliberately failed to disclose highly material evidence. There was simply no basis on which the judge could properly have concluded that the Claimant had simply got confused on these issues. The only possible reasonable inference from the evidence was that the Claimant intentionally failed to make full disclosure, and that failure can only be labelled as dishonest’.

The judge went on to determine that the claim was ‘fundamentally dishonest’ and allowed the defendant’s application:

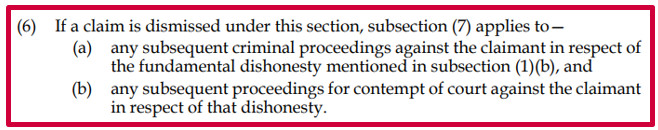

‘The dishonesty in question did not relate to some collateral matter, but went to the root of a substantial part of the claim ... Part of the purpose of a statement of truth is to bring home to party signing the solemn nature of what s/he is doing, and importance of telling the truth. To knowingly give a false statement of truth is a contempt of court: CPR r 17.6(1). By doing as he did, the Claimant prevented the Defendant from carrying out a proper investigation ... This skewed and distorted the presentation of his claim in a way that can only be termed fundamentally dishonest’.

In this way, ‘the judge was wrong not to have concluded (per CPR r 44.16(1)) that the claim was not fundamentally dishonest so as to allow the order for costs made against the Claimant to be enforced to its full extent’.

Full text judgment can be accessed here.

Even though the non-disclosure, in the present case, was related to the claimant’s alleged impecuniosity, which could not be assessed by the County Court and could have had a direct effect on the claimant’s acquisition of a replacement vehicle, vis-à-vis a credit hire company, the appeal Judge’s comments on ‘fundamental dishonesty’ are applicable to personal injury claims, generally.

What is more, pre-emption of civil contempt as a persuasive CPR 44.16(1) argument demonstrates the ever-blurring line between ‘fundamental dishonesty’, capable of claim dismissal, and ‘fundamental dishonesty’, capable of QOCS disapplication.

As Knowles J hypothesised, in LOCOG:

‘... it will be rare for a claim to be fundamentally dishonest without the claimant also being fundamentally dishonest, although that might be a theoretical possibility, at least’.

Essentially, therefore, Haider makes the compelling argument that it would be an unusual circumstance, in theory, for a s.57(1)(b) argument to succeed and a CPR 44.16(1) argument to fail, in the same set of proceedings.