INTRODUCTION

We reported in edition 160 of BC Disease News that according to a new study published this month, working night shifts has ‘little or no effect’ on a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer.[i] This was the conclusion of a new review by researchers at the University of Oxford that pooled evidence from three large UK-based studies, each of which found no significant link between night shift work for any number of years and breast cancer[ii].

In this article we will look at this topic more closely and consider the evidence which links night shift work with cancer in order to determine if there is in fact an occupational risk in the UK. We will also consider the guidance which is available for employers to reduce this risk.

MEDICAL EVIDENCE

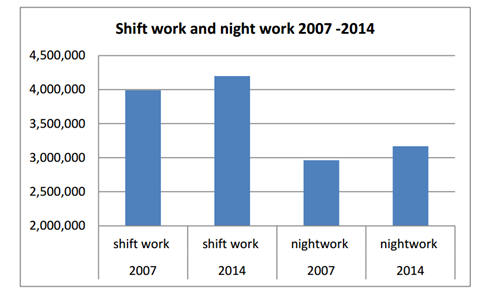

Around 14 percent of the working population (3.6 million people) report to working shifts 'most of the time'.[iii] Approximately 12.3% of all UK employees work nights. This is a 6.9% increase on the number of night shift workers in 2007.[iv] Such work is most prevalent in the healthcare, industrial manufacturing, mining, transport, communication, leisure and hospitality sectors. It used to be that night workers were mainly men in manufacturing plants and whilst men are still more likely to be night workers, the number of women working nights is growing at a much faster rate. Regular night working by women has increased by 12% since 2007. In several sectors, including social and health care, the number of women night workers is considerably greater than the number of men.

Image Source: TUC ‘A Hard Day’s Night’

In 2007, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified shift work with circadian disruption i.e. disruption to an individual’s body clock, as a group 2A carcinogen, or ‘probably carcinogenic to humans’. [v] It has been suggested that night shift work disrupts levels of the hormone melatonin, which has been suggested as having cancer protective properties.

The IARCs classification of shift work in 2007, also found that among the many different patterns of shift work, those with night work are the most disruptive to the circadian system. The IARC reported that epidemiological studies have found that long-term night workers had a higher risk of breast cancer than women who do not work at night. These studies involved mainly nurses and flight attendants. Six of eight epidemiological studies from various geographical regions, most notably two independent studies of nurses engaged in shift work at night, noted a modestly increased risk of breast cancer in long-term employees compared with those who are not engaged in shift work at night. Incidence of breast cancer was also modestly increased in most cohorts of female flight attendants, who also experience circadian disruption by frequently crossing time zones. The studies of humans are consistent with animal studies that demonstrate that constant light, dim light at night, or simulated chronic jet lag can substantially increase tumour development.

The aviation industry has an intense interest in research in this area, and the Aerospace Medical Association recommends frequent rests during shifts, including napping.[vi] Unfortunately, it also concludes that the major differences in individual responses to sleep loss, sleep disruption, and time zone transitions make it impossible to develop a ‘one size fits all’ shift schedule.

Other experimental studies show that reducing melatonin levels at night increases the incidence or growth of tumours. Exposure to light at night can disrupt the circadian system, which can alter sleep-activity patterns, suppress melatonin production and deregulate genes involved in tumour development. However, limitations in the data include the possible influence of confounding factors, inconsistent definitions of shift work, and the restriction of studies to nurses and flight attendants.

Several major studies have been published since the IARC classification. In 2010, Pronk and colleagues published a study in which 73,049 women in China were studied.[vii] At baseline, information on lifetime occupational history was collected, and night shift exposures were estimated by the researchers. Over a 2-year period, self-reported data on frequency and duration of shift work was also collected. Breast cancer incidence at follow-up an average of 9 years later was investigated. Breast cancer risk was not associated with ever working the night shifts on the basis of the job exposure estimation or self-reported history of night shifts, and risk was not associated with frequency, duration or cumulative amount of night shift work.

Hansen and Lassen compared 218 cases of breast cancer with 899 controls within a group of Danish female military employees.[viii] They found that the relative risk tended to increase with increasing number of years of night shift work and with cumulative number of shifts. Risks were also greater in those working three or more nights per week than in those working fewer than three times per week.

In 2013, a Canadian study that considered women working in many different roles found that women who had worked night shifts for 30 years or more were twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who had not.[ix] The association held for alternative definitions of prolonged shift work, with similar results for healthcare workers and other workers (previous studies tended to be restricted to nurses). No link was found between breast cancer risk and 0-14 or 15-29 years of night shift work. It is hypothesised in this study that night shift workers going from a day environment to an artificial light environment at night would have lower melatonin levels. This may increase the production of oestrogen, which is involved in the development of two in every three cases of breast cancer. However, the results of this study regarding the effects of hormones on cancer development were inconclusive. Although, the design of this study required participants to recall their past occupations and patterns of shift work, over lengthy periods in some cases, which might have led to inaccuracies. It is also possible that lifestyle factors related to night shift work may contribute to a higher breast cancer risk, though the researchers attempted to account for such factors in their analysis.

Since 2007, there has been extensive new evidence from studies in humans and also extensive new studies on mechanisms.

Most recently, this month, a new study, by researchers at the University of Oxford, found that night shift work, including long-term shift work, has little or no effect on breast cancer incidence[x]. The review pooled evidence from three large UK studies, each of which found no significant link between night shift work for any number of years and breast cancer, and seven studies identified by the IARC in 2007. The three new UK studies had large numbers of participants; 522,246 in the Million Women Study, 22,559 in the EPIC-Oxford study and 251,045 from UK Biobank. In each study, participants answered questions on shift work and were subsequently followed via records linked to the NHS Central Registers which provide information on cancer registrations and deaths. The outcomes of interest in this analysis were the first diagnosis of breast cancer or death from breast cancer.

Overall, it was found across the three studies, that there was no significant link between night shift work for any number of years and risk of breast cancer. Even when combining these results with the seven non-UK studies included in the previous 2007 IARC review, there was still no evidence that night shift work was associated with breast cancer. All the studies included in the analysis are observational, so the possibility that other health and lifestyle factors associated with night shift work, such as obesity or smoking, could increase breast cancer risk cannot be ruled out. As some of the results were of borderline statistical significance, the researchers state that a possible link cannot be ruled out. They also consider that a link could be found with longer follow-ups and larger study populations.

Further research on this topic has also been called for by the IARC, who in a document published in 2014, classed shift work as ‘high priority’ for evaluation towards the end of the 2015-2019 period, to maximise the quantity of evidence available.[xi]

OCCUPATIONAL DISEASE?

In Denmark in 2008, the Department of Occupational Injuries and Diseases decided to recognise cases of breast cancer as industrial injuries on certain conditions. In 2008, in 38 out of 75 cases, breast cancer after night shift work was recognised as an industrial injury, and compensation was granted in all cases except one. The injured person typically had night shift work for at least 20-30 years and at least once a week, and no other significant factors that might explain the development of breast cancer were present.[xii] In 2014, the department examined the correlation between night work and breast cancer again and considered that there was not sufficient medical knowledge to confirm the existence of a link between night work and breast cancer for women who, over 25 years, have been exposed to night work at most once a week. On the other hand, for cases of several night shifts per week over a period of 25 years, cases will be examined individually.[xiii]

In the UK, the Industrial Injuries Advisory Council (IIAC) considered the association between shift working and breast cancer in 2008,[xiv] following the Danish decision, and again in 2013.[xv] The 2008 review found little evidence that shift work could increase the risk of breast cancer sufficiently to allow attribution to work in the individual applicant on the balance of probabilities. The 2013 review found that, when some newer studies with large numbers of participants were considered, there is the possibility of a moderately elevated risk of breast cancer associated with prolonged (more than 20 years) of night work. However, a causal association is by no means firmly established, and there is insufficient evidence of an effect of magnitude that would support prescription.

What can employers do to keep the risk of shift work causing ill-health to their employees to a minimum? Several bodies and authorities have provided guidance on this issue.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EMPLOYERS

In 2006, HSE published the book, ‘Managing shift work Health and safety guidance’[xvi]. The guidance aims to improve safety and reduce ill health by:

The guidance aims to reduce problems related to sleep disturbance and fatigue, and only briefly mentions the possible link between shift work and breast cancer. This guidance is not necessarily the most suitable advice, as it was written about the risks as they were known 10 years ago. It does not answer questions that employers and unions may have about shift work, such as whether rotating shifts or permanent night shifts are preferable[xvii]. Hugh Robertson, the Senior Policy Officer for Health and Safety at the Trades Union Congress (TUC) comments in an article from July 2015 that there is a need for clear strong advice, sooner rather than later, on shift working.[xviii]

The TUC published a report in August 2015 on night work patterns and their effect on work/life balance.[xix] The report makes various recommendations, one of which is that UK employers meet their legal obligations to provide night workers with free health assessments. Under the Working Time Regulations 1998, a night worker’s average normal hours of work must not exceed 8 hours for each 24 hour period,[xx] and night workers should receive free health assessments.[xxi] The TUC vulnerable worker project found evidence that many industries were ignoring both these requirements.[xxii]

Other recommendations from the TUC report are:

Unite has published a guide for members regarding shift work and night work, which was revised in October 2013.[xxiii] Unite is campaigning for an extension of turnaround times on health and safety grounds, and for an amendment to the Civil Aviation (Working Time) Regulations 2004 to ensure compulsory breaks for cabin crew are taken free from any duty and away from passengers. They also worked to produce joint guidance Tower Crane Working Conditions Best Practice Guidance, which gives advice on timing of shifts, a requirement to provide a relief operator where necessary and other issues. The leaflet offers suggested guidelines for shift design, such as:

CONCLUSION

The link between shift work (in particular night shifts) and cancer is a very active area of research. Though some epidemiological studies suggest that there is a link between night shift work and breast cancer, others suggest there is no link, a conclusion which has been very recently confirmed by a study carried out by the University of Oxford.

Due to this uncertain medical evidence, shift work is yet to become a prescribed occupational disease in the UK. However, it is generally accepted that there is enough evidence to conclude that night shifts do pose some possible health risks to workers. The risk may be related to duration of time spent working night shifts, frequency of night shifts, or both. However, in many instances, the causal factors are unknown. As such, employers should continue to heed the advice available in order to minimise the risk of ill-health through shift work as much as possible.

This topic should be monitored closely, because if further research tends to suggest an effect, there are large numbers of employees who might be considered to be at risk.

[i] NHS Choices ‘No link’ between night shifts and breast cancer risk - Health News - NHS Choices. (2016). Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/news/2016/10October/Pages/No-link-between-night-shifts-and-breast-cancer-risk.aspx. (Accessed: 22nd October 2016)

[ii] Travis, R. C. et al. Night Shift Work and Breast Cancer Incidence: Three Prospective Studies and Meta-analysis of Published Studies. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 108, djw169 (2016).

[iii] ACAS, ‘Working The Night Shift: Practical Solutions To Longstanding Problems’ (ACAS March 2016)< http://www.acas.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=3877> accessed 31 October 2016.

[iv] Trade Union Congress, ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ (TUC August 2015)< https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/AHardDaysNight.pdf> accessed 31 October 2016.

[v] International Agency for Research on Cancer, Press Release 180, 5 December 2007, IARC Monographs Programme finds cancer hazards associated with shiftwork, painting and firefighting https://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/pr/2007/pr180.html

[vi] Caldwell JA, Mallis MM, Caldwell JL, Paul MA, Miller JC, Neri DF; Aerospace Medical Association Fatigue Countermeasures Subcommittee of the Aerospace Human Factors Committee. Fatigue countermeasures in aviation. Aviat Space Environ Med 2009;80:29-59.

[vii] Pronk, A. et al. Night-Shift Work and Breast Cancer Risk in a Cohort of Chinese Women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 171, 953–959 (2010).

[viii] Hansen, J. & Lassen, C. F. Nested case–control study of night shift work and breast cancer risk among women in the Danish military. Occup Environ Med 69, 551–556 (2012).

[ix] Grundy, A. et al. Increased risk of breast cancer associated with long-term shift work in Canada. Occup Environ Med oemed–2013–101482 (2013). doi:10.1136/oemed-2013-101482.

[x] Travis, R. C. et al. Night Shift Work and Breast Cancer Incidence: Three Prospective Studies and Meta-analysis of Published Studies. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 108, djw169 (2016).

[xi] IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Internal Report 14/002, Report of the Advisory Group to Recommend Priorities for IARC Monographs during 2015-2019, 18-19 April 2014. https://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Publications/internrep/14-002.pdf (Accessed 24th October 2016)

[xii] Many recognised cases of breast cancer after night. Available at: http://aes.dk/en/English/News/News-archive/Night-shift-work-and-the-risk-of-breast-/Many-recognised-cases-of-breast-cancer-a.aspx. (Accessed: 24th October 2016).

[xiii] DENMARK: Revision of the criteria for recognition of breast cancer related to night work. Available at: http://www.eurogip.fr/en/eurogip-infos-news?id=3733. (Accessed: 24th October 2016).

[xiv] The Industrial Injuries Advisory Council, Position paper 25, The association between shift working and (i) breast cancer (ii) ischaemic heart disease https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/shift-working-effects-on-breast-cancer-and-ischaemic-heart-disease-iiac-position-paper-25 (Accessed 24th October 2016).

[xv] The Industrial Injuries Advisory Council, Position paper 30, The association between shift working and breast cancer – an updated report https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/328502/shift-work-breast-cancer-iiac-pp-30.pdf (Accessed 24th October 2016).

[xvi] HSE Books, Managing Shiftwork Health and safety guidance, HSG 256, 2006 http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/priced/hsg256.pdf (Accessed 26 October 2016).

[xvii] Stronger Unions, What can we do about shift work? 23 July 2015 http://strongerunions.org/2015/07/23/what-can-we-do-about-shift-work/ (Accessed 26th October 2016).

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] TUC A Hard Day’s Night, The effect of night shift work on work/life balance, August 2015 https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/AHardDaysNight.pdf.

[xx] Night working hours - GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/night-working-hours/hours-and-limits. (Accessed: 26th October 2016).

[xxi] Night working hours - GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/night-working-hours/health-assessments. (Accessed: 26th October 2016).

[xxii] Vulnerable Workers Project www.vulnerableworkersproject.org.uk (Accessed 26th October 2016)

[xxiii] Unite guide for members, Shift work and night work http://www.unitetheunion.org/uploaded/documents/ShiftandNightWork%2011-4950.pdf (Accessed 26th October 2016).