INTRODUCTION

Last week we considered asymmetrical hearing loss (AHL) in the context of recent medical studies which consider whether asymmetry is a consequence of noise exposure and if so when.

This week we turn to look at how the courts have dealt with asymmetry with a review of the relevant case law

THE COLES GUIDELINES

Unexplained cases of asymmetry are considered in the guidelines at Note 11 which states: ‘In yet other cases, there is no apparent explanation for the presence of a significant NIHL-like notch or bulge on one side only. These cases are compatible with the presence of NIHL but with varying degrees of probability’.

Some examples of each of the 4 types of asymmetry are presented below:

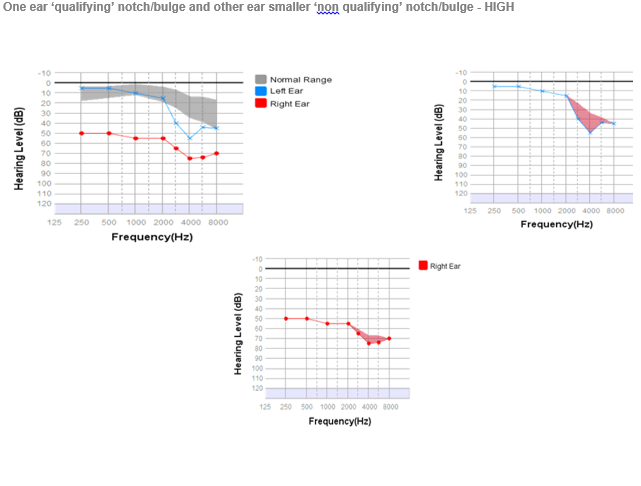

Asymmetry Type 1

‘….if one ear meets R3(a) or R3(b), and the other ear also shows a notch or bulge but it is smaller than the 10 dB or 20 dB required, then the probability of NIHL is still high’.

We show such a case in the figures below. The first figure shows the thresholds in both ears and compares these with a range of ‘normal hearing’ for the non-noise exposed population (for the claimant’s age / gender) as shown by the grey shaded area. The left ear is clearly the ‘better ear’. The red shading in figures 2 and 3 show worse than expected hearing applying the calculation within the Guidelines. The left ear in figure 2 demonstrates a clear audiometric bulge greater than 10 dB [for the purpose of this example assume R2(a) is satisfied under the Guidelines with a NIL of at least 100 dB(A)]. The worse right ear in figure 3 shows a bulge of 7dB-so not qualifying as a bulge within the Guidelines (see paragraphs 7.5, 7.6 and 8.2).

The Guidelines are ambiguous in that:

Asymmetry type 2

‘If one ear is markedly better at high frequencies and shows a significant notch or bulge, but the worse ear shows little or no trace of such, then there is still a more-likely than-not probability of NIHL’.

The Guidelines explain that ‘the greater impairment in the worse ear may be due to some unidentified cause additional to NIHL and ordinary AAHL, that additional disorder having hidden or obliterated the noise-induced notch or bulge’.

We show such a case in the figures below-the green shading in figure 3 denotes better than expected hearing after applying the calculation within the Guidelines.

Asymmetry type 3

‘In other cases there is not much difference between the two ears at high frequencies but, without apparent explanation, only one ear shows a significant notch or bulge and the other shows little or no trace of one: such cases should be regarded as very borderline and be decided on the strength of other evidence (e.g. severity of noise exposure or of temporary postexposure symptoms).

Such a case is shown in the figures below-although again there is ambiguity within the Guidelines as to what is meant by a ‘little’ notch or bulge.

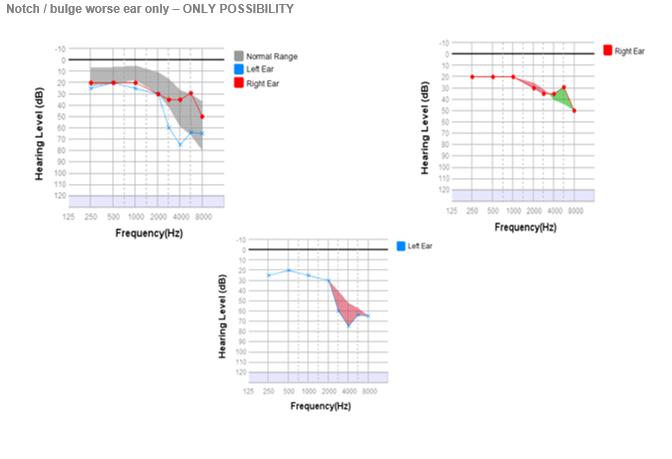

Asymmetry type 4

‘Finally, if only the worse ear at high frequencies shows a significant notch or bulge, and there is little or no trace of NIHL in the better ear, then there is only a possibility of NIHL, not a probability.

Again there is ambiguity as to what is meant by ‘little’.

An example of such a case is shown in the figures below where there is a notch/bulge in the worse left ear but no evidence of the same in the better right ear.

HOW HAVE THE COURTS DEALT WITH ASYMMETRY?

Perhaps the case in which asymmetry is most discussed is that of Cran v Perkins Engines Company Limited (14th December 2012, Norwich County Court). The defendant in this claim accepted breach of duty and as such the critical issue between the parties was whether the claimant’s hearing loss was caused by occupational noise exposure.

The evidence was confined to expert medical evidence from the two expert witnesses, Mr Lancer for the claimant and Mr Parker for the defendant.

The claimant had undergone audiograms in 1984, 1986, 1988 and 1990 (the audiograms carried out in 2010 and 2011 were disregarded as both experts agreed that they did not show features typical of NIHL and so had no evidential value in relation to the claim). The table below displays the results of the audiograms:

|

|

1984 |

1986 |

1988 |

1990 |

|

Left Ear (worse ear) |

Between 40-50dB at 6kHz. Notching. |

Significant notch at 6kHz with recovery at 8kHz. |

Notch at 4kHz but not at 6kHz. |

Very deep notch up to 8kHz. |

|

Right Ear (better ear) |

Between 10-15 dB at 6kHz. |

No notch at 6kHz or any other higher frequency. |

No notching. |

Some notching at 3-4kHz. |

It can be seen from these results that the claimant’s hearing loss would fall into asymmetry type 4, as outlined above i.e. only the worse ear at high frequencies showed a significant notch or bulge, and there was little or no trace of NIHL in the better ear’. According to the Coles guidelines, this presents only a ‘possibility’ of NIHL.

Both experts relied upon the approach to asymmetry in the Coles Guidelines, they also considered many of the studies that we outlined in last week’s feature in edition 165 of BCDN here.

Mr Lancer in particular, argued that the claimant’s hearing loss fell within Note 11, showing that NIHL was shown on the balance of probability, or alternatively, that the asymmetrical pattern of the hearing loss could justify a finding of NIHL. This conclusion, he said, was based on the study of Fernandes and Fernandes (2010),[1] which suggested that asymmetry did occur when there was ‘all over noise’. We touched on this study briefly last week as part of a wider examination of research purporting to link asymmetrical hearing loss with occupational noise exposure.

Fernandes (2010) investigated 208 clients referred by legal practitioners for assessment of hearing loss for compensation purposes. A total of 47 clients (22.6 %) had asymmetrical hearing loss. AHL was defined as loss of 10 dB or greater for two consecutive frequencies, or of 15 dB for any one frequency between 0.25 and 6 kHz. Diagnosis of NIHL was based on the requisite history of ‘substantial noise exposure at work’, audiogram results showing a hearing shift at high frequencies with a typical notch at 4-6 kHz and elimination of competing diagnoses. This study concluded that most compensation claims with asymmetry could be attributed to noise exposure. Within the paper, the researchers also referred to the Lutman and Coles study,[2] in which it was found that 1 % of non noise-exposed individuals had a defined asymmetric hearing loss. The argument presented by Fernandes is that incidence of asymmetric hearing loss in an unexposed population is therefore significantly low and incidence among noise-exposed groups is much higher, and thus the noise exposure causes the asymmetrical hearing loss.

In Mr Lancer’s opinion, this and other studies such as Alberti (1979), Chung et al (1983), Barrs (1994) and Segal (2007), supported his view that despite the asymmetry shown on the claimant’s audiograms, he had suffered NIHL (these studies were discussed in last week’s feature here. With the exception of Segal which is outlined in further detail below). This is because, he said, in a workplace there might appear to be all over noise but in fact there might be reverberations of machines which can lead to one ear receiving more noise than the other ear and the ears not recovering equally from exposure to noise.

Mr Parker, expert for the defendant, however, referred to the earliest audiogram test in 1984 which showed ‘distinct notch formation’ at 6kHz in the left ear (the worse ear) but not repeated on the right. He contended that the presence of asymmetry meant, in his opinion that this was not NIHL. Further to this, he said that as time went on the audiograms showed increased hearing loss in the left ear with an asymmetric notch at 4-6khz not being present on the right side which meant that the hearing loss was ‘not representative of occupational noise exposure’.

Mr Parker said that his opinion was supported by the Coles guidance and Note 11 specifically which said that if only the worse ear at high frequencies showed a significant notch or bulge and there was little or no trace of NIHL in the better ear then NIHL was a ‘possibility’ not a ‘probability’.

When considering Mr Lancer’s reliance on the Fernandes paper Mr Parker submitted that the definition of asymmetry used within the Fernandes paper, loss of 10 dB or greater for two consecutive frequencies, or of 15 dB for any one frequency between 0.2 and 6 kHz, was not really asymmetry and that they had a very low hurdle for describing an audiogram as asymmetric which would explain the high levels of AHL in the noise-exposed population. Whereas Coles and Lutman’s definition of asymmetry, a difference of 15 dB in the average of thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz, is far more exclusive than the definition used by Fernandes and thus Lutman and Coles’ criterion would be expected to give a smaller prevalence. He therefore remained of the opinion that asymmetry had nothing to do with noise. He referred to the Fernandes study as a ‘bad report’ and suggested that 200 cases or so had been pulled off the shelf by the authors who had decided that the individuals had been noise deafened. Further to this, he said that the claimant’s situation was very different from truck drivers (the sample group in the Fernandes paper) who were a well-accepted group who suffered asymmetrical exposure while driving a truck where the engine emitting significant noise had been in the cab next to the driver.

Mr Parker then went on to consider the studies of Alberti (1979), Chung et al (1983), Barrs (1994) and Segal (2007). All of these studies, suggest that asymmetry can be a consequence of general occupational noise exposure. Segal (2007), comprised a random selection of 429 patients with mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss of at leatst 30dB at one frequency. The authors found that age, handedness and sex were not found to be correlated to asymmetric hearing loss. However, a correlation was found between noise exposure and asymmetrical hearing loss which favoured the right ear (lower hearing threshold loss). The left ear hearing threshold was consistently found to the higher than the right ear hearing threshold level with hearing asymmetry of more than 10db found in 35% of these patients. However, noise exposure was the only factor which was found to correlate with asymmetric hearing loss in these patients with mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss.

Mr Parker claimed that, the authors of the papers had concluded that there had been NIHL based on inadequate consideration of the individual characteristics of those who had participated in the surveys including the incidence (or otherwise) of unilateral exposure. The better methodology, he claimed, would have been for a panel of experienced clinicians to have appraised each of the work histories and then to have made a diagnosis from the audiometry. As such, the weight of evidence and research did not show the susceptibility of one ear to noise and he remained of the view that there was no NIHL unless there was bilateral exposure and bilateral deterioration of the hearing in each ear.

His Honour Judge Staite, criticised the approach of Mr Lancer to the evidence of hearing loss put before him. He stated at para 50, that Mr Lancer had arrived ‘at a conclusion on liability in relation to NIHL which was at best superficial and at worst inaccurate…’.

Further to this he stated that:

‘In my judgment, Mr Lancer, having been advised that the claimant had been exposed to excessive noise levels during his working life and having concluded that the bilateral hearing loss in 2010 was too great to be accounted for by ageing alone, proceeded to make an assumption (which I find was unjustified on the presenting evidence ) that “his (the claimant’s) noisy occupations have made a contribution to the hearing loss” and furthermore that it was his “absolute belief” that excessive noise had contributed to the hearing loss’.

It was noted that during oral evidence Mr Lancer conceded that due to the absence of diagnostic factors in the four audiograms and having regard to the asymmetrical presentation of the claimant’s hearing that that evidence of noise exposure and unexplained hearing loss created a ‘possibility’ of NIHL rather than a ‘probability’. As such, the judge rejected the claimant’s submission that the audiograms complied with Note 11(1) and (2) i.e. NIHL was ‘more than likely’ or ‘very borderline’.

Instead, HHJ Staite, much preferred the evidence of Mr Parker in this regard stating at para 54:

‘Having heard both experts I was entirely persuaded by Mr Parker’s careful medico-scientific analysis of the issues in the case and his firm assertion that notches in the left ear which were not reproduced in the right ear during the exposure made a diagnosis of NIHL only one of serveral possible explanations for the claimant’s hearing loss’.

Turning his attention to the research papers relied upon in this case, the judge pointed out the difficulty with the Fernandes paper, in that it used the Lutman and Coles 2009 paper as a comparison but the cohorts compared were incomparable due to the differing definitions of asymmetry. As such he concluded that the comparison was inappropriate. He was also not sufficiently impressed with the other research papers relied upon:

‘I do not find therefore that the Fernandes paper [nor indeed any of the other papers] provided a sufficiently cogent analysis of asymmetric hearing loss. Nor do I find that the conclusion of the Fernandes paper was sufficiently sound for me to be persuaded that the concluded view (in the absence of other significant clinical history or evidence of otological disease asymmetrical hearing loss is caused by noise exposure and should be included in compensation claims) should be adopted by this court as evidence for the proposition that symmetrical noise exposure might, on balance of probability, cause asymmetrical hearing loss’.

As such HHJ Staite concluded that:

‘I am entirely satisfied, having regard to the Coles guidelines (which I find should inform my evaluation of the likelihood or otherwise of NIHL in this case) that the claimant has not made out his case on causation of NIHL and that save for the isolated notches on the 1986 and 1988 audiograms (which may be unreliable and are based on an adjusted reading at 6khz), there is insufficient evidence before the court to justify a finding of ‘probable’ NIHL as opposed to ‘possible’ NIHL. Accordingly, Note 11 (1-3) of the Coles guidelines is not satisfied and I find that the claim sits squarely within Note 11 (4)’.

Another judgment which discussed asymmetry in some detail and was handed down in the same year as Cran was, Aldred v Cortaulds Northern Textiles Limited (County Court Liverpool, 2 November 2012). The claimant in this case was a 61 year old female, employed with the defendant for between 11-14 years as a ring spinner machine operator. It was not accepted by the defendant that any noise exposure during her time at the firm had caused damage to her hearing but instead they contended that it was caused by an unknown origin. One of the main foundations of this argument was that the audiograms, of which there were several, showed significant AHL.

The audiograms were taken at several stages spanning from shortly after the claimant had ceased working with the defendant and right up to trial. These audiograms were then assessed by Mr Zeitoun, medical expert for the claimant, and Mr Parker, medical expert for the defendant.

|

|

1996 |

2006 |

June 2007 |

Nov 2007 |

Nov 2010 |

|

Left (worse ear) |

Modest bulges at 3kHz and 4khz. |

Left ear was worse than the right with a degree of AHL. Parker unable to support diagnosis of NIHL. Zeitoun did not disagree. |

Notches at 4kHz depicted a perfect audiogram for NIHL. Zeitoun agreed this was unreliable. |

Some conductive loss. |

Modest bulge at 3 and 4 kHz. 8.4 dB. |

|

Right (better ear) |

Modest bulges at 4kHz and 6kHz. |

Notch at 6kHz. |

Modest bulge at 3 and 4 kHz. 9.2 dB |

Following these audiograms, Mr O’Driscoll, a dedicated audiological scientist, carried out a series of audiometric testing and included the use of evoked response audiometry (CERA) and two pure tone audiometry (PTA) tests. Mr Parker then tested the outcome in accordance with the requirements set out in the guidelines and found:

|

|

August 2011 |

Nov 2011 |

|

Left |

Bulge at 4kHz. |

Slightly better hearing at 3kHz. |

|

Right |

No bulge. |

Slightly better hearing at 2kHz. |

Both experts were questioned about their interpretation of the guidelines in relation to asymmetry.

Mr Parker submitted that where he was faced with type 1 asymmetry (above) where one ear meets R3(a) or R3(b) and the other ear also shows a notch or bulge but is smaller than the 10dBs or 20dBs required but the probability of NIHL is ‘still high’ – he could not diagnose NIHL because of the incongruence of such a modest bulge in the better ear. Although he was prepared to accept that type 2 could indicate NIHL, where the ear with a significant notch or bulge had a significant degree of high-frequency recovery even though there was no evidence of either in the worse ear.

Mr Zeitoun however was strictly adherent to the guidelines and his assessment (using averaging which we discussed previously in edition xx) of the two audiograms came within asymmetry type 1.

The judge, HHJ Wood, accepted that there was asymmetry and so Note 11 was relevant. However, he rejected Mr Parker’s challenge to the probability of type 1 asymmetry in the guidelines concluding that it was reasonable to average the two tests carried out by Mr O’Driscoll which applied a slightly more generous allowance of -3dBs for the determination of the bulge and so the claimant did fit within type 1 and accordingly he found that there was a ‘high probability of NIHL’.

As such, he preferred the evidence of Mr Zeitoun and held that the claimant had satisfied him on the balance of probabilities that she has a modest hearing loss more pronounced on the left-hand side than the right hand side.

This decision was followed shortly by Sutton v BT (County Court Cardiff, 14 June 2013) in which asymmetry was one of several contentious issues relating to the diagnosis of NIHL of the claimant.

The claimant in this case submitted in oral evidence that his right ear was the more exposed ear during his time working with the defendant. However, the criteria set out in the guidelines were not met in the right ear and were only met in the left ear at 3kHz with ‘minimal notching. It was therefore submitted by the defendant’s expert, Mr Yeoh, that given the claimant’s pattern of use of the equipment, that this loss was unlikely to be the result of noise exposure. Additionally he said, the pattern was one which the guidelines, particularly Note 11, would regard as ‘very borderline’. HHJ Curran QC, preferred the approach of the defendant and found that not only was the claimant’s evidence unreliable but the bilateral condition for NIHL was not fulfilled, even allowing for an acceptable degree of asymmetry.

More recently in the decision of Briggs v RHM Frozen Food (Sheffield County Court, 30 July 2015) the topic was given some consideration. The audiograms showed a loss in the right ear of 10dB at 1kHz, 15dB at 2 kHz, 5dB at 3 kHz and 30dB at 4 kHz. In the left ear the figures were 15dB, 5dB, 5dB and 45dB.

|

|

1kHz |

2kHz |

3kHz |

4kHz |

|

Left Ear (better ear) |

15dB at 1kHz

|

5dB at 2kHz

|

5dB at 3kHz

|

45dB at 4kHz |

|

Right Ear (worse ear) |

10db at 1kHz

|

15dB at 2kHz

|

5dB at 3kHz

|

30dB at 4kHz |

Professor Homer, medical expert for the claimant, concluded that all the basic criteria for a diagnosis of NIHL were met by reference to the guidelines and that there was no significant asymmetry overall. He acknowledged that there is a commonly accepted margin of error of 10dB (plus or minus 5dB) but noted that the difference in this case at 4kHz was greater than that. He also pointed out that the generally accepted clinical definition of significant asymmetry is 15dB in two or more contiguous frequencies. Professor Homer was therefore adopting Fernandes’ definition of asymmetry (as outlined above).

Mr Jones, medical expert for the defendant, concluded that the hearing loss in the left ear could not be due to noise because it was too severe and because of the marked asymmetry. He disagreed with the suggestion that 15dB is not significant and found that asymmetry of 15dB is too significant to be attributable to symmetrical noise exposure and there would have to have been an idiopathic cause for the hearing loss.

HHJ Coe QC, agreed with Professor Homer and found that on a balance of probability that:

‘…whilst the asymmetry at 4 kHz is very much at the upper end of what is acceptable it is not beyond that and does not constitute “significant asymmetry”. Of itself, therefore, I do not consider that it is either inconsistent or so inconsistent with that expected in NIHL as to negate the diagnosis’.

CONCLUSION

The recent studies of Dobie (2014) and Phillips (2016) (as discussed last week) undermine the association between AHL and occupational noise exposure and show that typically asymmetrical hearing loss has other causes such as age, or even unknown causes.

The most comprehensive judicial review of the material in relation to asymmetry and occupational noise exposure is found in Cran. The decision shows that the available research when properly analysed, supports the argument that an NIHL diagnosis is strongest where there is bilateral hearing loss.

Whilst the decisions of Briggs and Aldred seem to contradict this conclusion in both cases the degree of asymmetry was modest and arguably could fall within the parameters of expected audiometric variability between the ears. It must also be remembered that individual findings on medical issues are fact specific and dependent on the nature and quality of medical evidence and authorities present in each case. As was cautioned in Childs v Brass & Alloy Pressings (Deritend) Ltd (21 December 2015), a de minimis case, where DJ Kelly made the following statement regarding the reliance on previous de minimis decisions:

‘It is apparent from those three cases that the conclusion as to whether or not the loss is de minimis is very fact specific to an individual case.

We warned in edition 133 of BC Disease News, that first instance decisions are of no precedent value as county court decisions are not binding. Further to this each decision is based on the particular evidence of each case. Findings on the evidence in one case is not a proper basis for the same finding in another case where the evidence is different. As such, it is difficult to extract any generally applicable principles from these first instance decisions on asymmetry and so defendants (and claimants) should not simply rely on previous favourable decisions without evidence to challenge those areas in dispute.

[1] Fernandes, S. V. & Fernandes, C. M. Medicolegal significance of asymmetrical hearing loss in cases of industrial noise exposure. J. Laryngol. Amp Otol. 124, 1051–1055 (2010).

[2] Lutman, M. E. & Coles, R. A. Asymmetric sensorineural hearing thresholds in the non-noise-exposed UK population: a retrospective analysis. Clin. Otolaryngol. 34, 316–321 (2009).