INTRODUCTION

In last week’s feature we looked at the potential dangers of reliance upon single audiograms for the diagnosis of NIHL. We concluded that single audiometry is likely to result in over-diagnosis of NIHL, lead to reduced repudiation rates and more claims paid which would provide cash flow to claimant organisations and in turn re-ignite a currently declining market.

This week, we consider the approaches adopted in NIHL claims where multiple audiograms have been available.

IS THE AUDIOGRAM ACCURATE?

Where there is more than one audiogram in a NIHL claim the first question to ask is whether the audiograms are reliable. It may be that one (or both or more) of the audiograms is not a genuine measure of the claimant’s hearing thresholds.

We considered the numerous factors which may cause an audiogram to be inaccurate in last week’s feature and which may lead to errors and variability in hearing thresholds. Medical convention accepts variability of 10dB in hearing thresholds between 2 hearing tests carried out closely in time as audiometry is not a precise science even when properly conducted.

Where there are multiple audiograms, where one (or both) is not properly conducted then the margin of error and variability in measured thresholds between tests can be far greater than the ‘acceptable margin of error’ of up to 10dB. [In last week’s feature we examined the recent ‘Solent University Studies’ which suggest that variability between even properly conducted tests may in fact be greater than 10dB].

Whilst some sources of audiometric error can result in better than actual hearing, the vast majority of errors however increase the measured hearing thresholds i.e. show hearing worse than it actually is. As stated by Lawton (1991)[i]:

‘…systemic errors [in pure tone audiometry] usually work to elevate the threshold, to make the hearing appear less acute than it really is’.

So where you have 2 audiograms carried out closely in time it follows that it is the audiogram which shows the best hearing thresholds which should be accepted as being more accurate and the best measure of a claimant’s hearing thresholds. Identifying inaccurate audiograms can be more troublesome where those audiograms are conducted many years apart. This was the case in Ross v Lyjon Company Limited (23rd September 2016, Liverpool County Court), which was featured in edition 157 of BC Disease News here.

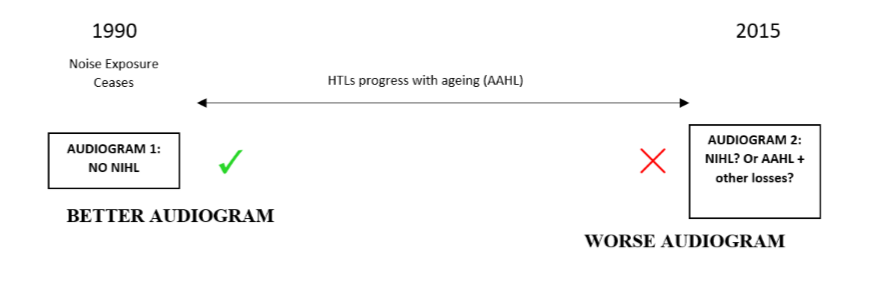

We illustrate this in our scenarios below involving a hypothetical claimant exposed to excessive noise in breach of duty with exposure ceasing in 1990. In both scenarios the claimant undergoes audiometry on cessation of exposure in 1990 and again in 2015 when presenting a NIHL claim.

In scenario 1 the 1990 audiogram shows no NIHL but the 2015 audiogram shows audiometric evidence of NIHL

In scenario 2 the 1990 audiogram shows NIHL but the 2015 audiogram shows no NIHL. Let us now consider these scenarios.

SCENARIO 1

Despite there being no more noise exposure between 1990 and 2015, the 2015 audiogram shows audiometric evidence of NIHL but the 1990 audiogram shows normal hearing on cessation of exposure. Medical convention is that NIHL is non-progressive. It doesn’t get worse once exposure ceases. The claimant might argue, as they did in Ross, that the earlier audiogram must be inaccurate and, in fact, the claimant had NIHL in 1990 (or argue for latency of onset of NIHL). However, it is often difficult to show that historic audiometry was not properly conducted in the absence of any proper evidence. This is even more so where an audiogram shows normal hearing. If the audiometry was not properly conducted one would expect audiometric errors to show worse than actual hearing. If a poorly conducted audiogram does not show NIHL then a claimant certainly doesn’t have NIHL.

Instead, one should consider whether the 2015 audiogram, which purportedly shows NIHL, is inaccurate and therefore showing hearing worse than it actually is. Alternatively, it could be that the audiogram is accurate but there are other causal factors-and not NIHL - resulting in losses worse than expected for age.

SCENARIO 2

We now reverse the position in scenario 2 with the 1990 audiogram apparently showing NIHL and the 2015 showing normal hearing. NIHL is a permanent condition. If it was present in 1990 it must be present today. If the 2015 audiogram does not show NIHL then it is either unreliable, or if it is reliable, then the 1990 audiogram must be unreliable (or there was a temporary cause of conductive hearing loss) and the claimant did not (and does not) have NIHL then.

AVERAGING AUDIOGRAMS?

The above scenarios relate to audiograms spaced widely over time and one of the audiograms being patently inaccurate or losses which cannot be attributable to NIHL.

How do we deal with audiograms which are performed closer in time-say within 1 to 2 years of each other and which, in theory, should show hearing thresholds within margins of acceptable audiometric variability and 10dB of each other at corresponding frequencies?

Can the results of these audiograms be averaged to provide a composite audiogram with the thresholds being the average of the two?

The CLB. (2000) ‘Guidelines on the diagnosis of noise-induced hearing loss for medicolegal purposes’,[ii] state at Note 3:

‘If an average of two, several or many hearing threshold measurements at the relevant frequencies in a particular ear can validly be used, the “at least 10dB or greater” guideline may be reduced slightly, by up to about 3dB. In borderline cases, an average of all the audiograms available and acceptable for averaging should be used in assessing the evidence for or against the presence of a high-frequency hearing impairment, notch or bulge.’ [Emphasis added].

Therefore the guidelines state that if you are able to average the results of more than one audiogram then the diagnostic threshold in R3a i.e. that there be a notch or bulge in the audiogram of 10dB, may be reduced to 7dB. Naturally then, this issue is intrinsic to diagnosis.

As can be seen from the extract of Note 3 above, averaging of audiograms is only recommended in certain circumstances and unfortunately, the guidelines do not explain when audiograms ‘can validly be used’ or are ‘acceptable for averaging’.

There has been and remains much debate regarding when averaging of audiograms may be utilised. We will now go on to consider these issues and then consider the impact this has on the diagnosis of NIHL.

Professor Lutman (one of the principle authors of the CLB Guidelines), in open correspondence to questions arising from the ambiguity of averaging, initially indicated that audiograms should only be averaged if they agree closely with one another. He further stated that it would be unlikely that audiograms obtained on different occasions, especially if they were obtained under different test conditions and with different equipment, would agree closely enough to make averaging meaningful and this is what is meant by the phrase ‘acceptable for averaging’ in Note 3. Therefore, his approach was that Note 3 should not normally be applied to the average of audiograms obtained on different occasions or by different examiners. In other words averaging was restricted to audiograms obtained at the same sitting and presumably designed to identify any intra-test variability.

However, his approach since appears to extend to allow averaging of audiograms which are carried out at different times, as long as the audiograms are similar and are not ‘intrinsically different’. By this we assume that hearing thresholds between the audiograms should be within 10dB of each other.

Professor Cole, again as a principle author of the original guidelines, has stated in open correspondence, that it is acceptable to average audiograms over a period of ten years provided there has been ‘no major audiometric changes over the period concerned’. Again, there is no definition of ‘major audiometric change’. We assume this means that the hearing thresholds have not deteriorated beyond what would be accepted for normal AAHL over the period.

Other experts-such as Mr Jones and Mr Parker-appear to be more circumspect about the principle of averaging on the basis that errors between tests tend to be largely systemic rather than random and the use of averaging lowers the burden of proof required for a diagnosis of NIHL. Alternatively, if averaging is to be considered then it should be restricted to tests with the same sitting and where these closely agree.

Errors in an audiometric measurement can be either systematic or random. A systematic error is an error that is constant or proportional across all measurements, for example, if an instrument is not calibrated correctly, all measurements may be 5 units larger than the ‘true’ values. ‘True’ readings may be calculated if the size and nature of the systematic error is known. A random error will be different across all measurements, sometimes resulting in lower or higher readings (and they will be higher or lower by different amounts) than the ‘true’ reading, and the ‘true’ reading may be determined by taking averages of multiple measurements. The greater part of the random error is usually attributable to judgement variability on the part of the person being tested[iii].

The impact that this has on averaging is illustrated by the review carried out by Lawton,[iv] which found that both systematic and random errors are present in the determination of auditory thresholds. Though random errors can result in thresholds appearing either higher or lower than they actually are, the authors report, systematic errors usually elevate the threshold, making the hearing appear poorer than it really is. So effectively in averaging you are at risk of simply combining the results from an accurate test with the elevated results from an inaccurate test-with the average also being greater than a true average. To compound matters that inaccurate average is then compared against a reduced diagnostic R3a threshold of 7dB to establish a diagnosis. There is little guidance within the case law on averaging.

In Aldred v Cortaulds Northern Textiles Limited,[v] the court was asked for the first time to consider the concept of averaging hearing threshold levels from different audiograms where minimal notching / bulging was present on some and not on others.

Mr Zeitoun for the claimant and Mr Parker for the defendant, disagreed on the meaning of ‘an average of all the audiograms available and acceptable for averaging’ as per Note 3. Mr Parker did not accept that this could apply to historic audiograms or those which were separated by distance in time. He claimed that he had discussed the approach with some of the authors of the guidelines and felt that re-testing was intended to be a reference to further cycles through the frequencies at the same sitting or test, rather than subsequent audiograms.

Mr Zeitoun also claimed to have discussed the approach of averaging audiograms with one of the authors and was of the firm stance that the use of audiograms from different days was perfectly acceptable.

HHJ Wood QC found that he preferred the approach of Mr Zeitoun as he felt it was ‘both logical and sensible that the guidelines should be interpreted to allow, within reason, the use of audiograms take at different times, and not within the same test setting’. He went on to say at para 26:

‘Apart from the obvious point made that the guidelines would have specified the exclusion of tests taken at more than one sitting (and elsewhere the advice is specific and proscribed), as one reads note 3, there are key indicators as to why this should be the case. First of all there is a reference to “many hearing threshold measurements”. It is difficult to see how this could contemplate such measurements being taken at one sitting. Second the qualification for providing a retest comes after a conclusion that a case is borderline and provides a specific process for repositioning the headphones. If the guideline authors have intended that this should be the reference to one or more of multiple tests then in my judgment it would have been stipulated’.

It should be noted that the audiograms in Aldred 2 audiograms spaced only 3 months apart and which were significantly similar were relied upon to find a diagnosis of NIHL. What is the approach to be taken when this is not the case?

In the de minimis decision of Harbison v The Rover Company Limited, discussed earlier in this edition of BC Disease News, it is probable that the averaging of 2 significantly different audiograms allowed a diagnosis of NIHL to be established where it did not in fact exist.

The claimant had undergone two audiograms, the first in May 2014 and the second in September 2015. The first audiogram showed a Coles compliant notch at 4kHz, however, the second audiogram did not with the hearing threshold level at 4kHz improving from 40dB to 20dB. However, to diagnose NIHL, Mr Sharma averaged the results for the right ear of both audiograms. After doing this, NIHL was found per Coles with a resulting 12dB audiometric bulge at 6 kHz satisfying a reduced R3a requirement of 7dB.

The defendant submitted that averaging of the audiograms was inappropriate as the hearing thresholds between the two differed by 20dB which was significantly more than the margin of acceptable audiometric variability of 10dB.The later 2015 audiogram demonstrated a significant improvement in thresholds which was not consistent with NIHL.

However in the absence of any medical evidence from the defendant, HHJ Carmel Wall stated:

‘In considering the strength of this argument I have regard to the fact that Mr Sharma was not challenged as to the appropriateness of averaging the two audiogram results; and that he had justified this method by reference to the CLB guidelines. His approach was thus a recognised mainstream approach to multiple audiograms designed to improve reliability of outcome. In those circumstances I conclude that I should be slow to reject his approach where there is no expert evidence to suggest that he was wrong to take that approach in this case’.

The judge found that when averaging the results at 6 kHz this satisfied the CLB requirement and so the claimant has proved the diagnosis of NIHL.

Although averaging multiple audiograms was accepted in this instance, it should be noted that the defendant did not have its own expert evidence to counter the use of averaging where it appeared to be clearly inappropriate to do so.

CONCLUSION

As mentioned above, audiometric error may be random or systematic. Random error is helped by averaging, systematic error is not, and most audiological error is systematic and tends to exaggerate hearing loss.

Averaging would certainly seem more appropriate for audiograms obtained at the same test to reduce intra-test errors - such repeat testing is advocated within the BSA Recommended Procedures for Pure Tone Audiometry[vi].

There seems to be some disagreement amongst experts as to whether it is appropriate to average results from different tests performed at different times-albeit still relatively close in time. However, there does seem to be some consensus that it would only be appropriate to do so where those audiograms closely agree.

Surely averaging cannot be appropriate where thresholds between audiograms perfor['med closely in time –say within 1 or 2 years of each other-differ significantly and show differences greater than 10dB at corresponding frequencies. This method was adopted in Harbison and probably resulted in mis-diagnosis of NIHL.

In such cases it is arguably more appropriate to disregard the worse audiogram, as being less accurate, and rely on the better audiogram alone for diagnosis.

Finally it would appear to be even more fraught with difficulties to apply averaging of audiograms performed wide apart in time given how and why hearing thresholds might have deteriorated over time between the two.

[i] B.W. Lawton, ‘Perspectives On Normal And Near-Normal Hearing’ (University of Southampton, Report No 200, October 1991).

[ii] R.R.A. Coles, M.E. Lutman & J.T. Buffin (2000) Guidelines on the diagnosis of noise-induced hearing loss for medicolegal purposes, Clin. Otolaryngol. 2000, 25, 264-273.

[iv] Lawton, Institute of Sound and Vibration Research, Perspectives on Normal and Near-normal Hearing, B.W. Lawton, ISVR Technical Report No 200 October 1991

[v] (February 6 2013, Liverpool County Court).

[vi] British Society of Audiology, ‘Recommended Procedure: Pure-Tone Air-Conduction And Bone-Conduction Threshold Audiometry With And Without Masking’ (British Society of Audiology, 9th September 2011, Amended February 2012).