Many adults in the UK spend more than 7 hours a day sitting or lying (not including time spent sleeping), and this typically increases with age to 10 hours or more.[i] This total daily sedentary time is comprised of occupational, leisure-time, domestic, and transport-related sedentary time.

In this feature article we will focus predominantly on occupational sitting and the possible adverse health consequences associated with this. We will do this by analysing the available research which links sitting to conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, obesity and musculoskeletal disorders.

Prevalence of Sitting

A study carried out by Buckley JP et al, quotes data which suggests that on average office workers spend up to 75 per cent of the day sitting. Another recent study of workers in the Northern Ireland Civil Service found that men had a mean occupational sitting time of around 6 hours per day, and women almost 6 ½ hours per day. [ii]

If it is assumed that a typical working day includes 8 hours spent working and 8 hours spent not working, then the total potential for time spent sitting is split equally between work time and non-work time (in the UK, the average time spent working is 36.3 hours per week, and 42.7 hours per week among full time workers). [iii] An Australian study found that those in full time work spent more time sitting at work than recreationally, with a mean of 4.2 hours sitting at work and a mean of 2.9 hours sitting recreationally. [iv] A Dutch study found that the working population spent an average of 7 hours a day sitting, one third of which was at work. [v] Occupational groups and sectors differed significantly: the greatest amount of time spent sitting at work was among legislators and senior managers (181 minutes per day), followed by clerks (160 minutes per day), and the smallest amounts of time were among agricultural workers (74 minutes per day) and service workers (51 minutes per day). Thus, for full time employees in physically inactive jobs, occupational sitting is likely to be the largest contributor to overall daily sitting time. [vi]

Given the increasing technological changes in the home and workplace, it is possible that modern humans have not yet reached their most sedentary, and that the average time spent sitting each day may still increase. A recent Danish study found that between 1990 and 2010 the proportion of Danish workers who sat for at least three quarters of their work time gradually increased from 33.1 to 39.1 %, and that occupational sitting time increased by 18 %. [vii] It is estimated that in the United States the prevalence of sedentary jobs increased from 15 % in 1960 to 25 % of jobs in 2008. [viii]

Possible Health Effects of Sitting

In the past decade, research on the effects of sedentary behaviours i.e. prolonged sitting or lying down, as a health threat has increased exponentially and has shown that it may be associated with an increased risk of major health outcomes, including cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal disorders and type II diabetes. [ix]

It is thought excessive sitting slows the metabolism – which affects our ability to regulate blood sugar and blood pressure, and metabolise fat – and may cause weaker muscles and bones.

One of the largest pieces of research to date on the subject – involving almost 800,000 people – found that, compared with those who sat the least, people who sat the longest had a: [x]

This research comprised a systematic review and meta-analysis which summarised the results of all the observational studies that had looked at the association between the time spent sitting or lying down whilst awake and the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and death due to cardiovascular disease or any other cause.

Despite the fact that the studies were from a range of countries, and that each study was performed differently, the time spent sedentary was consistently associated with poorer health outcomes. However, this study cannot show that sedentary behaviour is the direct cause of the increases in risk as there may be other confounding factors associated with both sedentary behaviour and disease risk (for example smoking, alcohol, diet, or socioeconomic factors) which the individual studies may not all have taken into account.

For example, many of these conditions can also be linked with obesity. Whilst there has been research which suggests that excessive sitting is linked to obesity a 2008 study was able to establish that actually, being obese may cause sedentary time which is reversed causation from the assumption that sitting can cause obesity. [1]

Guidance for Employees and Employers

The strength of the evidence for a link between sitting and ill health is such that the World Health Organisation has published guidelines, adopted by Public Health England, which recommends 150 minutes of exercise a week in order to counter the effects of sitting, but some research suggests that even this is insufficient for some people. [xi]

A WHO spokesman said: ‘Recommendations related to sitting and sedentary behaviours are not available yet. However, WHO already recommends governments implement policy actions around making environments where people live and work more conducive to physical activity’.

The UK government issued new recommendations in 2011 on minimising sitting for different age groups.

The Start Active, Stay Active report published by the Department of Health recommends breaking up long periods of sitting time with ‘shorter bouts of activity for just one to two minutes’. A panel of leading experts who reviewed the evidence on sitting for the report recommended taking ‘an active break from sitting every 30 minutes’. [xii] The advice applies to everyone, even people who exercise regularly, because too much sitting is now recognised as an independent risk factor for ill health.

Ideally, to minimise the risk of adverse health effects, a worker should have the option to sit, stand, move around and vary the nature of work tasks. An expert statement commissioned by Public Health England and Active Working C.I.C., published in 2015, aimed to provide guidance for employers and staff working in office environments to combat the potential ills of long bouts of seated office work [xiii]. The core recommendations are as follows:

“For those occupations, which are predominantly desk-based, workers should aim to follow these recommendations:

The NHS also recommends the following to reduce sitting time [xiv]:

The HSE booklet ‘Seating at work’ (1997) offers guidance on the safety and suitability of workplace seating. [xv] The advice does not mention reduction of the amount of seated time, but focuses on how to make seating comfortable.

Stand-sit workstations and dynamic workstations have also been suggested as alternatives to sitting workstations. The purpose of such devices is to encourage workers to change working positions. They are used by over 90 % of office workers in Scandinavia and they can be easily adjusted to sitting or standing height. [xvi]

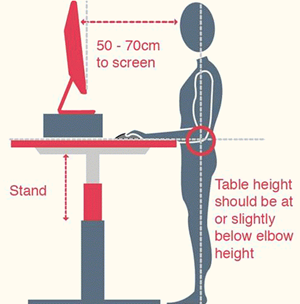

It is important when choosing a standing desk to ensure that it meets ergonomic requirements. Such requirements are illustrated in the figure below[xvii], and include:

Figure: Standing desk [xvii]

Less commonly used are treadmill workstations, these are desks attached to a treadmill, upon which the user walks whilst working.

Figure: Treadmill desk [xix]

According to Get Britain Standing, it is surprisingly easy to type and speak while walking at a slow pace, but is less easy to write by hand[xx]. Treadmill desks can be desks that are designed to cover a traditional treadmill, a treadmill that is designed to fit under a standing desk, and a treadmill with desk included.

Occupational v Leisure Sitting

It has been suggested that different types of sitting may have different relationships with health. This finding was reported by several studies. For example, Periera[xxi] found that television viewing was associated with more biomarkers for disease than occupational sitting.

In general, it appears that comparisons between occupational sitting and health effects may show fewer or weaker effects than comparisons between overall sitting and health effects, or television viewing and health effects. These differences may be due to socioeconomic factors, for example, sitting at work tends to be associated with higher socioeconomic status, whereas longer times watching television tend to be associated with lower socioeconomic status. Thus, differences in other variables that result from social status may influence the effects of time spent sitting on health.

Conclusion

Whilst there is some evidence which supports a link between prolonged sitting at work and conditions such as, heart disease and diabetes for any cause of action to be established, an individual would need to show that their occupation doubled the risk of contracting that condition.

In edition 53 we provided a feature which considered the association of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) with exposure to vibration at work. We noted that in the case of Ward v Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council (2013), the claimant could not prove that the use of vibration tools whilst at work doubled the risk of developing CTS and so it was held that the vibration had not been the cause of the claimant’s condition. The full feature can be accessed here. The same principles used in CTS can therefore be applied in claims for prolonged sitting whilst at work based on the research outlined in this article, that there is a lack of evidence that prolonged sitting doubles the risk of contracting the condition.

Next week we will be presenting a feature on the possible health consequences of prolonged occupational standing.

[1] Ekelund, U., Brage, S., Besson, H., Sharp, S. & Wareham, N. J. Time spent being sedentary and weight gain in healthy adults: reverse or bidirectional causality? Am J Clin Nutr 88, 612–617 (2008).

[i] Why sitting too much is bad for your health - Live Well - NHS Choices. (2016). Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/fitness/Pages/sitting-and-sedentary-behaviour-are-bad-for-your-health.aspx. (Accessed: 17th September 2016)

[ii] Munir, F. et al. Work engagement and its association with occupational sitting time: results from the Stormont study. BMC Public Health 15, (2015).

[iii] Office for National Statistics, Hours Worked in the Labour Market, 2011 http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160105160709/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_247259.pdf

[iv] Brown, W. J., Miller, Y. D. & Miller, R. Sitting time and work patterns as indicators of overweight and obesity in Australian adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27, 1340–1346 (2003).

[v] Jans, M. P., Proper, K. I. & Hildebrandt, V. H. Sedentary behavior in Dutch workers: differences between occupations and business sectors. Am J Prev Med 33, 450–454 (2007).

[vi] van Uffelen, J. G. Z. et al. Occupational Sitting and Health Risks. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 39, 379–388 (2010).

[vii] van der Ploeg, H. P., Møller, S. V., Hannerz, H., van der Beek, A. J. & Holtermann, A. Temporal changes in occupational sitting time in the Danish workforce and associations with all-cause mortality: results from the Danish work environment cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 12, (2015).

[viii] Church, T. S. et al. Trends over 5 Decades in U.S. Occupation-Related Physical Activity and Their Associations with Obesity. PLOS ONE 6, e19657 (2011).

[ix] H. Susan J Picavet et al, ‘The Relation Between Occupational Sitting and Mental, Cardiometabolic, and Musculoskeletal Health Over a Period Of 15 years – The Doetinchem Cohort Study’, PLoS One. 2016; 11(1): e0146639.

[x] van Uffelen, J. G. Z. et al. Occupational Sitting and Health Risks. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 39, 379–388 (2010).

[xi] Haroon Siddique, ‘One Hour Of Activity Needed to Offset Harmful Effects Of Sitting At A Desk’ (The Guardian 27 July 2016)< https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/jul/27/health-risk-one-hour-activity-offset-eight-hours-sitting-desk> accessed 14 October 2016.

[xii] https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216370/dh_128210.pdf

[xiii] Buckley, J. P. et al. The sedentary office: a growing case for change towards better health and productivity. Expert statement commissioned by Public Health England and the Active Working Community Interest Company. Br J Sports Med bjsports–2015–094618 (2015). doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094618

[xiv]Why sitting too much is bad for your health - Live Well - NHS Choices. (2016). Available at: http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/fitness/Pages/sitting-and-sedentary-behaviour-are-bad-for-your-health.aspx. (Accessed: 17th September 2016)

[xv] HSE Seating at work, 1997 http://www.hse.gov.uk/pubns/priced/hsg57.pdf

[xvi] Sit-Stand Solutions. Height Adjustable Desk, Variable Hight Desk, Treadmill Desk, Desk Riser, Desk Mount. Available at: http://www.getbritainstanding.org/solutions.php. (Accessed: 26th September 2016)

[xvii] Figure from http://www.getbritainstanding.org/start.php

[xviii] Image from https://nz.pinterest.com/dt538/standing-desk/

[xix] Image from http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/2013/11/best-treadmill-desks/index.htm

[xx] Sit-Stand Solutions. Height Adjustable Desk, Variable Hight Desk, Treadmill Desk, Desk Riser, Desk Mount. Available at: http://www.getbritainstanding.org/solutions.php. (Accessed: 26th September 2016)

[xxi] Pereira, S. M. P., Ki, M. & Power, C. Sedentary Behaviour and Biomarkers for Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes in Mid-Life: The Role of Television-Viewing and Sitting at Work. PLOS ONE 7, e31132 (2012).